This is one of many blog posts which will run for four days from 15th-19th August, 2013, celebrating Roman historical fiction…

…and there’s a prize for the most interesting comment!

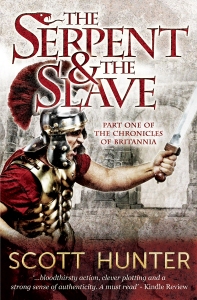

My novel, ‘The Serpent & The Slave’, is set in Britannia, in 367AD, a turbulent time of invasion which hinted at Rome’s loosening grip on our sceptred isle.

Below are my notes from the afterword which I hope you will find intriguing!

At the time of the great ‘Barbarian Conspiracy’ of 367 AD, Valentinian was the emperor of the West. Historians reckon that such an invasion would have required a coordinator of some stature; someone familiar not only with the structure and strength of Roman military deployments but also with a keen understanding of which political issues were likely to affect the emperor’s judgement. Paulus Catena certainly fits the bill and it seemed rather a waste to allow the man known as The Chain to rest in peace after his execution in Africa.

In terms of the ‘look and feel’ of fourth century Britain, I have tried to paint as accurate a picture as possible.

The provinces were divided as described, Corinium being the capital of Britannia Prima. Interestingly, there was indeed a fourth century governor by the name of Lucius Septimius, although I cannot claim that the character described in ‘The Serpent and the Slave’ bears any resemblance to the original, save for the fact that the real Lucius was also a dedicated pagan. We know this because he is noted as making an ‘almost aggressively pagan dedication at Corinium’ by Peter Salway in his excellent work, ‘Roman Britain’. The Alamann chieftain, Fraomar, also has a real counterpart in an Alamannic chieftain who was sent to Britain in 372. Salway confirms this to be a known fact and I quote: ‘Fraomar was in fact sent to Britain as a deliberate act of Imperial favour by Valentinian 1 as a military tribune to command a normal Roman unit of Alamanni already stationed in the island’.

Religion

The fourth century was a time of religious change. Constantine had legalized and formalized Christianity during his reign in the early years of the century but there was still a strong pagan tradition, particularly amongst the civil magistracy. The short reign of Magnentius whose tolerance, even encouragement, of pagan worship caused many to ‘come out’ and resume their old ways of worship led directly to the Pauline persecutions when Constantius gained control of Britain. No doubt there were many who simply continued their pagan practices in secret. Valentinian himself was of Christian persuasion, although I suspect that he, like so many others, could best be described as having a ‘nominal’ rather than a ‘life-changing’ faith, such as demonstrated by the character of Freia. Many slaves, the downtrodden members of a corrupt society, embraced the new religion as being one that offered hope, salvation and equality. What more could a slave wish for than this? Small wonder then that many found the answer they sought in the person of the humble rabbi from Galilee, Jesus Christ, the chosen one of God.

The Roman Army

The army saw many structural changes during the 3rd and 4th Centuries. The legions were redeployed and reabsorbed into two distinct groups, the limitanei, operating on the frontiers and the comitatenses, originally stationed with the emperor, but later becoming more of a mobile field army to be deployed as the need arose. The thinking behind this change was based on the premise that a reasonably well maintained border force combined with a high quality mobile army would be the most effective way to deal with the many and varied threats to the empire. Britannia did suffer from a degradation of troops as demand across the channel became more pressing, but the double defeats in 367AD of the Saxon Shore Count, Nectarides, and the dux Britanniarum, Fullofaudes, left the country vulnerable in the extreme to the invaders. Many Roman troops deserted after the defeats and took to wandering the countryside, no doubt undertaking a little plunder and pillage themselves. In ‘The Serpent and the Slave’, the character Scapulus and his men had awarded themselves ‘leave of absence’ from the army, and this is indeed what many of the army remnant actually did. It was only when Count Theodosius arrived late in 367AD and offered free pardon, food and supplies to any renegade troops wishing to give themselves up that the Britannic army began to reassemble itself into some sort of order. For the hapless ordinary folk of Britannia, particularly those living in the countryside, it must have been a very unpleasant and trying time to have lived through.

Excerpt from ‘The Serpent & The Slave’

The Rhine Frontier, Gaul – Sept 367AD

In the headquarters tent of the Rhine campaign, the Emperor Valentinian, arguably the most powerful man in the known world, leaned back with some discomfort on the curule, an elaborately carved oak seat inlaid with ivory. The chair had been especially commissioned for his imperial behind, and was the only obvious indication of his status, except perhaps for the imperial purple of his cloak. The emperor’s back was playing up again and he was not in a good mood. ‘Well?’ He barked at the tribune.

Well, don’t just stand there like a wilting vine, man. Show him in!’

‘Caesar.’ The tribune saluted and signalled to the tent guard.

The tent flap opened and a man entered. He had a pinched, hunted appearance in marked contrast to his speech, which was direct and confident. ‘You sent for me, Caesar?’

‘I did.’ The emperor stood up carefully with a grimace of pain. The seat was murdering his vertebrae. He drew a hand wearily across his eyes. ‘Nipius. I seem to remember that you had a hankering for foreign travel.’

‘Caesar?’ Nipius frowned.

‘I’ve had an interesting communication from Britannia. From Septimius in Corinium.’

Nipius raised an eyebrow quizzically.

‘They have, apparently, in custody a member of the royal Alamannic line. One named Fraomar. Ring any bells?’

‘Chnodomar’s brother. Went missing after Strasbourg.’

Valentinian nodded approvingly. ‘The same.’

‘We were outnumbered three to one,’ Nipius recalled, ‘but Julian led us to a great victory.’

Valentinian allowed himself a smile. ‘His gods certainly seemed to be with him that day. But I heard it was the Magister Equitum who deserves the credit for the victory.’

Nipius bowed stiffly. ‘Caesar is too kind.’

‘A shame that the victory of Strasbourg was marred by Fraomar’s escape.’

For the first time, Nipius seemed uncomfortable. Rain began to drum softly on the leather covering of the tent roof as Valentinian continued:

‘But you are a popular man, Nipius. Your exploits are legendary. You have – what can I say– ’ Valentinian stroked his chin thoughtfully, ‘a loyal following?’

‘I am fortunate enough to have the respect of my men, yes Caesar.’

Valentinian grunted. ‘Well, naturally I thought of you for this little job.’

‘What does Caesar command?’

‘A simple ‘go fetch’ job, nothing more. Give you a break. God knows you probably need one. And a chance to set the record straight.’

Nipius smiled thinly. ‘I am most grateful to Caesar.’

I hope you enjoyed this excerpt from ‘The Serpent & the Slave’, by Scott Hunter

Here are the other links for this Blog hop:

http://pillingswritingcorner.blogspot.co.uk/

http://elisabethstorrs.blogspot.com.au/

http://www.gordondoherty.co.uk/writeblog/

http://mark-patton.blogspot.co.uk/

http://wordpress.mcscott.co.uk

http://teacake421.livejournal.com

http://themasterofverona.typepad.com/the_master_of_verona/

http://alison-morton.com/blog/

http://petreaburchard.com/blog-2/

http://timhodkinson.blogspot.com/

Dominus mihi adjutor

.

Enjoyed this article – looks an interesting book too!

Thanks Helen! I enjoyed your Arthurian slant very much.

I’m picturing these big, mean, Roman marauders going AWOL and tromping around Pasadena, California. Indeed, right around 366 AD, Britain would have been uncomfortable, to say the least.

Just ordered your book – sounds like an exciting read, and set in the exact same year and place as mine. Can’t wait to see how you portray the ‘Barbarian Conspiracy’ – the historical evidence is so vague, a novelist can have quite a bit of fun with it!

Thanks John! Hope you enjoy it!